Friends,

Please join me on my new website at EmptyPath.net.

All the content from this blog has been duplicated there, and that is where I will publish new material.

Blessings,

Mike

Nonaligned faith and practice in the present

Friends,

Please join me on my new website at EmptyPath.net.

All the content from this blog has been duplicated there, and that is where I will publish new material.

Blessings,

Mike

“I believe God loves those moments when we do without him. He thinks, ‘At last, they’re going to stop walking around with their nose up in the air awaiting some supernatural magic; they’re going to watch the snow and the trees and start to think a bit. They’re doing the job without me, inventing utopias that don’t have me as their essence; they are finding within themselves there reason for all things. In fact, without realizing it, they are understanding my Law, for it is the Law of the world’.”

— Joann Sfar, author of The Rabbi’s Cat,

in the afterword to Klezmer, Book One: Tales of the Wild West

See https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/articles/1539/drawing-conclusions-joann-sfar-and-the-jews-of-france/.

In 2015, writing about “Christian Universalisms,” I explained that Jesus

was from Galilee in northern Palestine, child of Aramaic-speaking peasants, not of the “proper” Hebrew-speaking Jews from Judea in the south. His [initial] concern was that his own Galilean people not feel excluded from God’s blessing because of their not being part of the Jerusalem-centered Temple cult.

As we find in teaching stories like “the woman at the well” (John 4) and “the man who fell among thieves” (Luke 10:25-37), Jesus gradually also engaged himself—and, hence, his followers—with the Samaritans,

people whose land lay between Galilee and Judea. The Samaritans were mixed-race descendants of those scattered people who remained in Palestine when the Judean Hebrews were carried into exile in Babylon. They were scorned by Judeans, due both to their mixed heritage and to their revering of Mount Gerizim rather than Jerusalem as God’s chosen worship site.

Even with this change, Jesus still limited himself to people who were somehow within the Hebrew cultic tradition. However, in both Mark (7:24-30) and Matthew (15:21-28) we are told of a journey to the Mediterranean coast during which he a met Canaanite woman.

In this context, “Canaanite” means one from among the mixture of races who had been in Canaan before the Hebrews conquered it. The translation of Mark used here calls the Canaanite woman a “Greek,” that is “a Gentile” or “Pagan.”

From there he got up and went away to the regions of Tyre. Whenever he visited a house he wanted no one to know, but he could not escape notice. Instead, suddenly a woman whose daughter had an unclean spirit heard about him, and came and fell down at his feet. The woman was a Greek, by race a Phoenician from Syria.

And she started asking him to drive the demon out of her daughter. He responded to her like this: “Let the children be fed first, since it isn’t good to take bread out of children’s mouths and throw it to the dogs!”

But as a rejoinder she says to him, “Sir, even the dogs under the table get to eat scraps (dropped by) children!”

Then he said to her, “For that retort, be on your way, the demon has come out of your daughter.”

She returned home and found the child lying on the bed and the demon was gone.

— Mark 7:24-30,

The Complete Gospels: Annotated Scholars Version,

Robert J. Miller, Editor (1994, p.30)

In her 2001 Ideas at the Powerhouse lecture, Elaine Wainwright, former Professor of Theology at the University of Auckland, re-imagines the story of the Canaanite woman (named “Justa” in later traditions) in the context of a story about an Australian Aboriginal woman who faced colonialist scorn.

Justa’s voice is constructed by the…storyteller, who sets her story in the context of the ancient Canaanite/Israelite struggle. Jesus, whose birth and life story generally placed him among the colonised of the Roman empire, preaching a message that was counter-Imperial, is placed in this story in the role of the coloniser.

He stands with and for ancient Israel, as this story evokes that of another conquest of land, namely ancient Israel’s violent appropriation of the land of the Canaanites on the grounds of its being promised as divine gift.

Wainwright continues by imagining the transformation Jesus might have experienced during this confrontation:

The Jesus of this new story-telling, this shaping of a new spiritual imagination, emerges, not in doctrinal or dogmatic formulae, but engaged in the process of recognizing his own complicity in colonialism, even while steeped in a broader life vision of seeking to eradicate it.

We are always unlearning and learning on this path toward transformation, and stories which remind us of this aspect of the journeying can sustain our spirits along the way.

In an earlier piece written for Reading from This Place. 2: Social Location and Biblical Interpretation Internationally (Fortress, 1995, pp. 151-52), Wainwright shares her feminist take on how this story might have been viewed by 2nd- and 3rd-generation Christians in the house churches of Antioch. Some of these communities were made up mostly of Aramaic-speaking Hebrews and others, mostly Greek-speaking Gentiles.

In an earlier piece written for Reading from This Place. 2: Social Location and Biblical Interpretation Internationally (Fortress, 1995, pp. 151-52), Wainwright shares her feminist take on how this story might have been viewed by 2nd- and 3rd-generation Christians in the house churches of Antioch. Some of these communities were made up mostly of Aramaic-speaking Hebrews and others, mostly Greek-speaking Gentiles.

Wainwright pictures leaders of these house churches meeting to gather together their various traditions about Jesus. On this occasion, they were retelling the story of the Canaanite woman. Miriam, representing a community where Greek- and Aramaic-speaking people worshiped together, was the first to speak.

She told it as the story of Justa, the woman of Tyre whose granddaughter was now a member of their community. Justa had told and retold the story of her encounter with Jesus….

Justa [had] called out for help to this itinerant Jew, who wandered into the area and who was being followed by such a close-knit group of women and men that he gave the appearance of being a holy one. How taken aback she was when she received this insulting rebuff: It is not fair to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs.

Justa’s need, however, was greater than any humiliation she could receive and so, led by some power even beyond her own consciousness, she quipped back: Ah, but even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their master’s table.

She remembered her own fear at the realisation of what she had just said, but also her experience of a new power which she had not known before, a power which would never again allow her to be put down in such a way.

She remembered also the look of astonishment, recognition and even shame that passed across the face of the Jewish holy man whom she later came to know as Jesus. He spontaneously held out his hand to her in welcome, drawing her up from her position of supplication, and he acclaimed her: Woman, great is your faith.

Miriam acknowledged that their community had extended the saying of Jesus: Let it be done for you as you desire, so as to highlight Jesus’ recognition of what Justa had taught him; a recognition that linked her insight into wholeness with that of God whose way, whose dream, Jesus was to establish on earth.

Johannan, leader of an Aramaic-speaking house church, interrupted.

You tell this story as if it were a story of Justa rather than Jesus. Our community is much more aware of the outrage that Jesus must have felt when confronted by this foreigner who was not only Syrophoenician—a veritable Canaanite according to our tradition—but also female.

We have it on good authority from those who knew Jesus’ companions of that day, that Jesus at first ignored the woman. He was forever faithful to the traditions of his religion and he would not have spoken to such a woman in public….

Furthermore, in the story as we received it from our Hellenistic Jewish brothers and sisters in southern Syria, Jesus is reported as saying to the woman: I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel. This is a very different picture of Jesus than that presented by Miriam.

Jesus may eventually have given the woman what she wanted because she was crying after them, as the disciples suggested, but the story still preserves the integrity of his mission to Israel rather than to the Gentiles, and our God-given gender distinctions.

Finally Justinian, a Roman official who led a Greek-speaking community, intervened.

Johannan, we have had this conversation many times before, I know, but Jesus’ own vision of his ministry was more universal than you say. This is one of our key stories which illustrate the movement within Jesus during his lifetime enabling him to see his mission as one including us.

This woman, whom we don’t name and I am happy to learn her name, this woman Justa, is indeed for us the foremother of the mission which includes us as Gentiles. Just as she won healing and wholeness for her daughter, so too she won it for us, her daughters and sons today.

While she does not have a name in our story, she does, however, have a voice. She addresses Jesus as ‘Kyrios’ and as ‘Son of David’ and she cries out in the language of prayer and liturgy: ‘have mercy on me’ and ‘help me.’

Indeed, for us, her voice echoes the voice of the women of our community who participate in the liturgical life of the community and in our theological reflection.

I hadn’t heard the conclusion to the story as Miriam has told it but I can tell you…it will be significant in our house community, and we will add it to our telling of the story, so you would do well to include it also.

And so it is.

Blessings,

Mike Shell

Christ and the Canaanite Woman, about 1650, Pen and brown ink, brown wash, corrected with white gouache, 20 × 27.9 cm (7 7/8 × 11 in). Unknown maker, Rembrandt Pupil, active 1650s. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. This image is available for download, without charge, under the Getty’s Open Content Program.

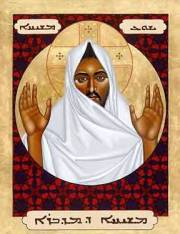

“Christ of the Desert,” icon by Brother Robert Lentz, OFB (available from Trinity Stores). Br. Lentz writes:

Out of the deserts of the Middle East comes an ancient Christian tradition. Although it has been overshadowed by the Greek and Latin traditions, it is their equal in dignity and theological importance. It is a Semitic tradition, belonging to those churches that use Syriac as their liturgical language. Syriac is a dialect of Aramaic, the language spoken by Christ himself.

This icon celebrates the richness of Syriac Christianity. The inscriptions in the upper corners read “Jesus Christ,” and at the bottom, “Christ of the Desert.” The Syriac language has ties to the earth that are deep and rich. It is more inclusive than most European languages. The theological experience of Syriac Christians is different because they have encountered the Gospel in such a language. Theirs is an unhellenized expression—one that is neither Europeanized nor Westernized.

Semitic as it is, the Syriac tradition knows no dichotomy between the mind and heart. The heart is the center of the human person—center of intellect as well as feelings. The body and all of creation longs to be reunited with God.

A constant theme in Syriac literature is homesickness for Paradise, a desire to restore Paradise on earth. Christians pray facing east because Paradise was in the east. This longing was expressed in monastic terms in ancient times, but its implications today reach far beyond monastery walls. With earthy roots, this longing for Paradise involves concrete responses in the realms of politics, ecology, and economics.

Many of us are chronically distressed by the suffering we see around us. It confronts us in the 24/7 news cycle, in social media, in what we pass on the street every day. We live with a longing to be rid of the pain and guilt that we experience in witnessing all of this suffering.

That longing drives us to cast about for things to do that would “fix the problem.” We try and we urge others to try political action. We give and we urge others to give. Even so, we still feel our discomfort and our seeming failure to accomplish a fix.

The Gospel of Mark tells us a story in which Jesus addresses this pain and guilt, yet we tend to miss his message—in part because centuries of tradition have focused so much on him rather than on what he was teaching us.

He was just reclining [at table], and a woman came in carrying an alabaster jar of myrrh, of pure and expensive nard. She broke the jar and poured [the myrrh his head.]

Now some of them were annoyed…. “What good purpose is served by this waste of myrrh? For she could have sold the myrrh for more than three hundred silver coins and given to the poor….”

Then Jesus said, “Let her alone. Why are you bothering her? She has done me a courtesy. Remember, there will always be the poor around, and whenever you want you can do good for them, but I won’t always be around. She did what she could—she anticipates in anointing my body for burial….”

— excerpts from Mark 14:3-9

The Complete Gospels: Annotated Scholars Version,

ed. by Robert J. Miller, Polebridge Press, 1994

At one level, this is a story about men who resent an independent woman wealthy enough to pour out an entire jar of nard. At the level of evangelical storytelling, it is the author of Mark pointing his audience toward the crucifixion of Jesus.

What interests me, though, is the paradoxical play of sacred story. Jesus is direct in his criticism of his friends: “There will always be the poor around, and whenever you want you can do good for them.” He is more subtle in his challenge.

Come back to the present moment. We are all with each other now. This woman is not afraid to acknowledge my mortality—or her own, or yours. Instead of distracting herself from that reality with worldly concerns, she is blessing me right now.

Quaker faith and practice internalizes the crucifixion. Each of us is invited to embrace the death of “the Christ within” which is our true self. Until we are able to do that, we continue to be distracted by fear of our own mortality.

How much can we truly serve others while we are so distracted?

Image source

Ointment pot, Egypt, 2000-100 BCE, L0065469 Credit Science Museum, London, Wellcome Images. Library reference no.: Science Museum A634855. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only license CC BY 4.0.

Egyptian vessels from this era vary in size and shape. Very small jars held expensive liquids such as opium suspended in oil. Large jars stored wine and household ingredients. The tapered bases of oil jars such as this could be pushed into the ground to keep the jar upright. This example is made from alabaster. Other materials used included wood, clay, metal and glass.

Originally published on Quaker Universalist Conversations (1/1/17).

I had a dream a few days ago, one of those rare wholly unambiguous dreams. It was a flying dream, but that’s not the relevant feature, just a plot device.

I was returning home to an upper floor of a six-story apartment building. Flying over the roof, I saw that the whole surface was filled with sleeping refugees. As I came down toward the building entrance I saw that all the yard and parking lot space was also crowded with refugee families.

I was returning home to an upper floor of a six-story apartment building. Flying over the roof, I saw that the whole surface was filled with sleeping refugees. As I came down toward the building entrance I saw that all the yard and parking lot space was also crowded with refugee families.

As I entered, several men asked me what I was going to do to help their families and neighbors. I made no excuses, but I acknowledged that, even if I sold everything and liquidated my bank accounts, I could only feed some of the many people for a few days. Then we would all remain together in the same destitution.

The dream ended inconclusively.

Knowing is overwhelming. Every day, more stories of slaughter and flight from slaughter. Every day, more encounters with street people, immigrants, and other hurting, marginalized neighbors. And every day, more evidence of siege mentality1 on the part of a public and political world on guard against the call of empathy.

My dream is not about this larger reaction against empathy but about my own. All beings avoid pain, and the most subversive version of this the attempt to avoid the pain of feeling the pain of others. We rush for “solutions” that will mask that empathetic pain—whether or not our actions really “help.” My dream challenges me to sit with my own pain of witnessing pain.

This morning in my stream-of-consciousness journal I received the following opening:

![“Forgiveness,” by Carlos Latuff [Copyrighted free use], via Wikimedia Commons](https://emptypath.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/forgiveness_1-180px.gif?w=490) You don’t have to know what to do next. In fact, you can’t. Trying to discern it is work that gets in the way of seeing it. Pay attention to the need, not the solution. Pay attention to how you feel about knowing of the need. Really settle into it.

You don’t have to know what to do next. In fact, you can’t. Trying to discern it is work that gets in the way of seeing it. Pay attention to the need, not the solution. Pay attention to how you feel about knowing of the need. Really settle into it.

What you are doing is exploring those inward defenses which stand in the way of your truly engaging with the person in need. So long as you avoid direct experience of your own conflicting feelings, those feelings are barriers to being truly open to the other person.

Compassion means feeling passion with another. Feelings come first.

And so it is.

Blessèd be,

Michael

Notes & Image Sources

1 “Siege Mentality,” by Daniel Bar-Tal, Beyond Intractability [Copyright © 2003-2016, The Beyond Intractability Project, The Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado].

One…interesting social-political-psychological phenomenon [is the shared misperception] of being under siege, i.e., feeling as if the rest of the world has highly negative intentions towards one’s own society or that one’s own society is surrounded by a hostile world…. “Negative intentions” refer to the desire and motivation of the world to inflict harm or to hurt the society, so that they imply a threat to the society’s well being.

Image of migrants on the northern Greek border from “As Europe struggles for a unified approach to the refugee crisis, tens of thousands of people remain stranded in Greece,” on AccessWDUN (3/7/2016).

Migrants wait by the border gate between Greece and Macedonia at the northern Greek border station of Idomeni, Monday, March 7, 2016. Greek police officials say Macedonian authorities have imposed further restrictions on refugees trying to cross the border, saying only those from cities they consider to be at war can enter as up to 14,000 people are trapped in Idomeni, while another 6,000-7,000 are being housed in refugee camps around the region. (AP Photo/Vadim Ghirda)

“Forgiveness,” by Carlos Latuff [Copyrighted free use], via Wikimedia Commons.